Fatimah sat on the living room couch in a split-level home in Surrey, B.C. Her three-year-old son played on the carpet with a toy train.

They arrived in Canada two months ago, through the government’s Afghan resettlement program, fleeing Taliban threats to the family over its work for the Canadian Forces.

But while they no longer have to worry the Taliban will come to the door to exact revenge, that safety came with a price.

Read more:

Inside the Kabul safe houses where Afghans wait to be evacuated to Canada

On the morning the family was being evacuated from Kabul airport on Aug. 25, Canadian officials told them they couldn’t all get on the flight, Fatimah said.

So they had to make a choice: risk staying together in Kabul, or separate. They were given until noon to make a decision.

They decided Fatimah would take their son, Abid, to Canada, and her husband Mohammad would stay in Afghanistan with their five-year-old daughter.

That way, at least part of the family would be safe.

Fatimah’s family at Kabul airport, Aug. 25, 2021.

Family Handout

“That day was very hard,” Fatimah said in an interview last week. “My daughter was crying after me, and my son was crying after his father.”

The family has remained divided ever since.

In Kabul, Global News interviewed Fatimah’s husband Mohammad, who similarly recalled the pain of watching his wife and son leave.

“That was a difficult moment,” he said.

Read more:

Hopes crushed by return of Taliban, Kabul women see no future in Afghanistan

Four months after the federal government vowed to resettle Afghans at risk under the Taliban, less than a tenth of the promised 40,000 have arrived.

Evacuations out of Kabul have stalled, and Afghans waiting to flee to Canada are frustrated at what they consider the sluggish pace of their applications.

Although many worked for the Canadian Forces in Kandahar, they said they were struggling to get answers from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

Even those accepted by the program haven’t been able to get out of Afghanistan.

Fatimah, left, watches over her son Abid, in Surrey, B.C., Nov. 17, 2021.

Stewart Bell/Global News

The government said 9,535 applications had been approved and extra immigration staff have been sent abroad to help.

“However, unlike previous refugee resettlement initiatives (such as Syria), there is no existing infrastructure to support our work,” said Alexander Cohen, Immigration Minister Sean Fraser’s spokesperson.

“This means that getting the program established is taking longer than in the past,” he said.

The government was also working with allies, neighbouring countries, NGOs and veterans to find ways to get refugees out of Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, Cohen said.

Since Canada stopped evacuations in August, more than 1,000 Afghans bound for Canada had escaped overland into neighbouring countries, he said.

Photo taken by Fatimah’s family at Kabul airport, Aug. 25, 2021.

Family Handout

But fewer than 4,000 Afghans have made it to Canada, government figures show. Thousands of others remain stranded inside Afghanistan.

That has been particularly hard for families that have been torn apart like Fatimah’s.

Thirteen members of her family share a house in Surrey, southeast of Vancouver. They have a roof over their heads and a well-stocked fridge, but they are missing the spouses and kids left behind.

Fatimah’s sister had to flee Kabul without her husband and three of her children. Three of Fatimah’s brothers are similarly without their wives and some of their kids.

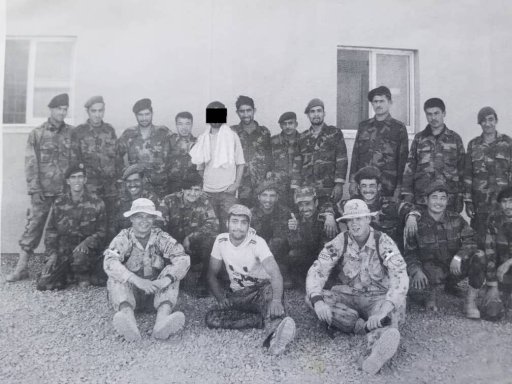

Abdul, centre with his face hidden to protect his identity, with the Canadian Forces in Kandahar.

Family Handout

The family said it was at risk after the Taliban came to power because two of the brothers worked as interpreters for the Canadian Forces in Kandahar.

Both moved to Canada in 2011 and are now Canadian citizens, but given the Taliban’s history of score-settling, they worried their siblings and parents were also in danger.

Fatimah’s brother Abdul said that after he began translating for the Canadians in 2007, the Taliban warned him twice to stop working for the “enemy.”

When he ignored them, a magnetic bomb was planted on his car. It exploded as he was approaching the vehicle, he said.

(Like the others in the family, he asked to be identified only by his first name because of the dangers faced by relatives still in Afghanistan.)

Taliban checkpoint in Kabul, Oct. 20, 2021.

Stewart Bell/Global News

Abdul moved to Canada in 2011 and now works in Vancouver’s film industry. But as the Taliban was advancing this year amid the U.S. military withdrawal, he returned to Afghanistan to try to get the rest of his family to safety.

While he was there, he helped out the Canadian Forces at Kabul airport as they tried to evacuate Canadian citizens and Afghans who had worked for the military and embassy, he said.

His family spent two days trying to get to the airport, where the crowds were packed so tight they kept losing hold of the kids, he said

Fatimah’s family waiting to board evacuation flight at Kabul airport, Aug. 25, 2021.

Family Handout

On the morning of Aug. 25, Abdul said the Canadian Forces told him Canada was suspending its evacuations and the last evacuation flight would be leaving that day.

But they also told him only his siblings would be allowed to board the military transport flight to Qatar, not their husbands or wives, he said.

“So then we had to make a decision,” he said. “It was a very tough situation, a very emotional situation.”

“Everyone was crying.”

He said he was able to convince the Canadian troops to at least take the youngest children, because they needed their mothers, but the rest had to stay behind.

Fatimah’s evacuation flight from Kabul.

Family Handout

Fatimah consoled herself with the thought that at least part of the family would be out of danger, and that her husband and daughter would soon be able to join her.

“It was hard for us,” she said.

But Fatimah’s husband Mohammad said his application to come to Canada was still in progress, and with no evacuation flights, there was little to hope, either for himself or the many others stuck in Kabul.

“Please speed up the process for them,” Mohammad said.

The Veterans Transition Network, which has been helping resettle Afghans who worked for the Canadian Forces, said further government action was needed.

“More needs to be done,” president Tim Laidler said. “And that’s why we’re still raising money at the VTN and still in communication with government to find a solution that sees the tens of thousands of people promised to come to Canada a way out of Afghanistan.”

Photo taken by Fatimah’s family in Qatar, before transiting to Canada.

Family Handout

More than two dozen members of Fatimah’s family remain on the run in Afghanistan.

For their protection, they keep on the move. They don’t stay at any one location for more than a week. They speak to their spouses over WhatsApp.

Abdul said he didn’t know what was holding up their cases, and he could not get answers from the government.

“So now we are worried about them,” he said. “Anything is possible over there, anything can happen to them.”

Photo taken by Fatimah’s family in Qatar shows a bus carrying Afghans to the airport for their flight to Canada.

Family Handout

Fatimah said she had been unable to sleep.

With her son on her knee, she called up a picture on her phone of her husband and daughter. She talks to the girl every day, she said.

“I miss her a lot and I want her to come here soon,” she said.

“Life is good here but if my husband and daughter and my parents come here, I will be very happy.”