The Vatican Museums are among the world’s most popular, featuring vast art collections, including masterpieces by Michelangelo and Raphael, and drawing more than six million visitors every year.

But one exhibit in Vatican City is garnering attention for the wrong reasons.

The Vatican’s Anima Mundi Ethnological Museum holds thousands of Indigenous artifacts that were taken from communities across Canada by Catholic missionaries a century ago. Indigenous Peoples have long called for the artifacts to be repatriated, and in 2022, Pope Francis pledged to finally return them to Canada.

But following his death in April and the election of Pope Leo XIV, Indigenous leaders now worry Pope Francis’s promise may die with him.

“It could just be swept under the rug,” said Gloria Bell, a Canadian art historian, author and assistant professor at McGill University, who has Metis ancestry. “These belongings were stolen from Indigenous communities.”

Indigenous wood carvings on display at the Vatican’s Anima Mundi Ethnological Museum.

Global News

In 1924, Pope Pius XI called on Catholic missionaries around the world to collect Indigenous artifacts and bring them to the Vatican. The following year, the artifacts were put on display as part of the Vatican’s Missionary Exhibition, a landmark event that promoted residential schools and the Church’s missions across the globe, which attracted around one million pilgrims and visitors.

The artifacts have since become a permanent collection at the Vatican. Global News toured the Amina Munda exhibit with Bell, who was on a visit to Rome to deliver lectures and expand her research on the artifacts’ origins.

The wide range of rare and priceless artifacts include a seal skin kayak and a wampum belt. Most of the items are currently held in storage, but dozens are on display. The Vatican exhibit calls them “gifts.”

“Calling everything a ‘gift’ is just a false narrative,” Bell said.

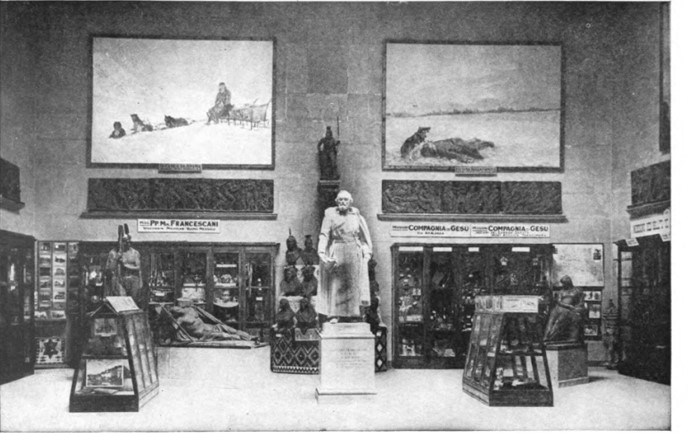

The Vatican Missionary Exhibition in 1925 promoted the Catholic Church’s residential schools and missions across the globe.

Provided by Gloria Bell

She pointed to an Australian Aboriginal activist, Anthony Martin Fernando, who held a one-man protest at St. Peter’s Square during the Vatican Missionary Exhibition in 1925, distributing thousands of leaflets that denounced how the artifacts had been stolen.

For his protest, Fernando was arrested and thrown in jail.

“Think of how everything was acquired by missionaries conducting their genocidal work in Indigenous communities in the 1920s, one of the most aggressive assimilative periods in the early 20th century, when these belongings were stolen from Indigenous communities,” Bell said.

“Indigenous children were held against their will in residential schools, and then their materials were put on display in this exhibition as ‘trophies’ of the pope.”

The Inuvialuit kayak, built a century ago in the Mackenzie Delta region, is being held in storage at the Vatican Museums.

Provided by Rosanne Casimir

In 2022, a delegation of Indigenous leaders from Canada were invited to Rome to meet Pope Francis and discuss reconciliation efforts. During their visit, as a goodwill gesture, Vatican officials privately showed the group some of the artifacts.

“Seeing these items that were made by the hands of, in many cases, women of our great-great-great grandmother’s generation, it was very moving, it was very profound,” said Victoria Purden, president of the Metis National Council, who was part of the delegation.

“You couldn’t help but feel that tug in your heart that those items should be back home. And they should be somewhere where our children and our grandchildren and our communities could enjoy them and contemplate them.”

In 2022, Pope Francis formally apologised to residential school survivors and promised the artifacts would be returned to their communities in Canada. Three years later, it’s unclear whether any progress has been made on the file.

“There’s a lot of rhetoric around truth and reconciliation, a lot of sort of performativity around it, but there hasn’t been any restitution to date,” Bell said.

Canadian Art Historian Gloria Bell and Global News reporter Jeff Semple on a tour of the Vatican’s Anima Mundi Ethnological Museum, which houses thousands of Indigenous artefacts.

Global News

The decision of whether to return the artifacts will now ultimately rest with the newly-elected Pope Leo XIV. Global News asked the Canadian Cardinals who participated in the Conclave that elected him whether they expect Pope Leo to fulfill his predecessor’s promise.

“The artifacts, the situation is something that I know is underway. There’s some reflection,” said Cardinal Gérald Lacroix, the Archbishop of Quebec. “Let’s let things unfold. But I’m sure (Pope Leo) will be interested in that.”

Purden, who returned to Vatican City for Pope Francis’s funeral and against raised the issue in a meeting with Vatican officials, said she remains optimistic that the artefacts will be returned to their communities.

“What an important symbol of reconciliation returning them will be when we managed to accomplish that,” she said.