It was a cold, crisp day in December 2016 when Ellen Watters climbed onto her aquamarine racing bicycle for the last time.

The 28-year-old was back home in Apohaqui, N.B., a rural community about 45 minutes outside of Saint John, for a much-deserved break.

After a successful 2016 that saw Watters hailed as a rising star in Canadian competitive cycling, she was looking forward to spending time with family and friends, who knew her as an energetic “people person” who was always full of spark.

Read more:

N.B. cyclists continue to push for Motor Vehicle Act amendments

It’s that energy and passion that kept Watters training and riding, even when she was supposed to be enjoying a holiday.

Her newest tool was the month-old Bianchi racing bike she was riding on Dec. 23, 2016. Despite a small amount of snow, she made good time. Eventually, she would begin travelling west along Riverview Drive East, a two-lane roadway.

It was on that road, just before 2:25 p.m., that the front bumper of a white Volkswagen Golf hit the rear wheel of Watters’ bicycle.

The force of the collision threw her body backward over the rear of the bicycle and into the windshield of the car, which then vaulted her body over the roof and onto the pavement.

She died five days later on Dec. 28 at the age of 28.

The incident sparked enough of an outcry for New Brunswick to pass legislation, “Ellen’s Law,” that aims to protect cyclists. Even so, the police investigation into the crash resulted in no charges, and the details of the RCMP’s report would remain hidden. Only now, after a federal access to information request that took three years, can Global News finally shed light on the police investigation into the crash.

Though heavily redacted, the RCMP report provides new information on what happened during the crash and raises questions on when the decision to not lay charges was made.

That decision not to charge the driver, Wayne Sabean of Digby, N.S., and the actions of those in power in the years following the crash have left the Watters family unsatisfied, while the cycling community says the eponymous law does not do enough to properly honour Ellen Watters’ legacy.

This story draws on interviews with Ellen Watters’ mother, the cycling community in New Brunswick and the previously unreleased RCMP crash report.

Friends of Ellen Watters sit with her mother, Nancy Watters (second from left).

Tim Roszell/Global News

Beginnings

The youngest of four children, Ellen is described by her mother as being a “people person” with an innate sense of adventure — even at a young age.

“She was always full of energy. And the more people that were around her, the more energy she could muster up,” Nancy Watters says at the family home in Apohaqui, which is located 64 kilometres northeast of Saint John.

“She would wake up, come down in the morning to say, ‘What are we going to do today?’” Nancy says.

“She really liked home but she also liked people, she was a people person.”

Sports quickly became a part of her life, with Ellen becoming interested in basketball despite no other kids in the neighbourhood playing.

“She didn’t know a soul who was going to be playing, but she just had it in their head that this was something she wanted to do,” Nancy says.

It was that type of drive that carried Ellen through the rest of her life, always ready to take on new challenges.

She would stay close to home even after she graduated from high school, living with her mother as she went to the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, a one and a half hour trip by car.

Nancy Watters sits at a memorial bench honouring her daughter, Ellen Watters, in Apohaqui, N.B.,

Tim Roszell/Global News

In 2009, Ellen would find a passion that would push her forward for the rest of her life.

Nancy and a friend had been training for a triathlon when two days ahead of the race Ellen asked to join.

Nancy finished at the back of the back — she recalls she might have been second to last. As for Ellen, without any training, she came in second place.

With that, Ellen was hooked. She competed in triathlons throughout the summer and eventually decided to stop with the swimming and compete only in duathlons.

She’d compete and win in a competition in Moncton — netting her the chance to compete at the world duathlon championships in Gijon, Spain, in 2011.

“We went to Spain that September and she came out of the arena after the running and cycling, and she said, ‘I don’t think I did very well at all,’” Nancy says.

Read more:

Advocates call for political parties to commit to modernizing New Brunswick’s Motor Vehicle Act

Her daughter was shocked to find out later that day that she came in third.

It was some time afterwards that Ellen decided to begin training and competing in competitive cycling. She’d join a development team that took her across Canada but also made her better.

In 2016, she’d placed first in the women’s category in the 2016 Kugler-Anderson Tour of Sommerville, an 80.5-kilometre race held in New Jersey at the end of May.

“It was a real feather in her cap,” Nancy says.

By the end of the year, Ellen had signed with the Union Cycliste Internationale women’s team Colavita/Bianchi for the upcoming 2017 season, finally becoming a professional cyclist.

She was determined to carve a path towards qualifying for the Canadian Olympic team.

Through it all, Ellen was a vocal advocate for road safety and openly talked to the media about the experiences cyclists had with cars.

Nancy recalls a conversation she had with her daughter that appears nearly prophetic in hindsight. Ellen was speaking about if she were ever in an accident that made the roads safer for cyclists.

“Ellen once said, ‘If by something happening to me, it would improve cycling safety on the road, I’d be fine with that.’”

Before the 2017 season began, Ellen decided to end 2016 with a trip home to New Brunswick.

Her professional career would end before she officially competed on the professional circuit.

The bike that was ridden by Ellen Watters on the day she died. It remains in her mother’s possession nearly four years later.

Tim Roszell/Global News

The crash

Nancy says that nearly four years later, her daughter’s death stills affects her.

Recalling the time she spent with her daughter and the memories they shared together is particularly painful. She wept when interviewed by Global News.

But it’s those memories that Nancy continues to hold onto. Even the physical items that remind Nancy of her daughter are hard to let go of.

The aquamarine bike that Ellen rode the day she died is still in one piece. Her mother has kept it despite the harsh reminder it brings her. The rear wheel is crushed beyond recognition. The spokes are collapsed. The left seat stay — the part connecting the body of the bike to its gears — is sheared off.

The bike, along with the crash report, tells the story of Ellen’s death.

Despite being heavily redacted, the report provides more information than has been previously released to the public regarding the crash. And in this first draft of history, the initial culprit was the sun.

Const. Rob Driscoll, the police officer who was the first to arrive at the scene, notes that as soon as he arrived, he was concerned about the effect of the sun on the scene.

“I had personally felt from the time of my initial arrival on the scene that the sun’s position could have played a role in reducing the driver’s visibility and was further concerned about the effect it would have on flowing traffic around the scene,” he wrote.

A photo of the Ellen Watters crash site on Dec. 23, 2016. First responders initially believed the sun had been a factor in the crash.

Cst. Rob Driscoll/RCMP

Driscoll would join witnesses and Wayne Sabean, the driver of the vehicle, as they waited for paramedics to arrive. It was only at that time that he would recognize the cyclist as the local celebrity, Ellen Watters.

A later analysis told a different story. A report by collision analyst, RCMP Sgt. Rick Younker would later conclude that despite first impressions, the sun should have had little to no effect on the Sabean’s field of view.

More importantly, Younker determined that the sun would not have obscured the man’s view of Ellen’s bicycle.

“Any resultant glare from the sun or the wet roadway surface of the eastbound lane, would have been within the driver’s left field of view and should not have obscured the view of the cyclist,” Younker’s report reads.

The report is clear that there were no other significant obstructions in the immediate area of the collision.

According to the report, the decision to not lay charges came on Dec. 28, 2016, the same day that Watters died.

Yet that decision wasn’t announced publicly until days after Ellen’s Law was passed in the provincial legislature on May 5, 2017.

“It’s determined that there is not sufficient evidence to support any charges,” RCMP Sgt. Jim MacPherson told Global News at the time.

Nancy says that before the RCMP announcement, investigators broadly hinted that she should be prepared for no charges to be laid but that it was still distressing to find out. It’s still something that she doesn’t understand, even today.

Nancy Watters at a memorial marking the location where Ellen Watters was struck and killed while riding her bicycle.

Tim Roszell/Global News

Accepting that she would never get her day in court has not come easy for Nancy. Even nearly four years later, answers aren’t available and they may never be.

New Brunswick’s Department of Justice would not provide responses to any questions about what went into its decision not to lay charges. The department cited the confidential and legal deliberations that go into any decision to press any charges.

Nancy insists that even if charges were laid she would not have wanted Sabean to go to jail. But at the very least, she says, she would have liked to have seen his driver’s licence taken away.

“I don’t want this fellow to go to jail or prison or whatever, but I want the society and the public to recognize that if they don’t pay attention when they’re driving and they cause an accident, then they need to be responsible in some way,” Nancy says.

For Nancy, the ability to find closure is fleeting.

She sued Sabean in 2018, alleging that he was driving “without due care and attention” when he struck Ellen.

In the statement of claim, Nancy Watters alleges the collision was caused “solely by the negligence of (Sabean) for striking the bicycle of Ellen Watters when his attention was distracted as he was trying to determine how to get to Riverview and onto the highway.”

Read more:

Mother of Ellen Watters files legal action against alleged driver

But the allegations were never to be tested in court. The case was withdrawn after Sabean died less than 10 days after it was filed, according to an obituary posted online.

Now, the only justice Nancy has left is ensuring what happened to her daughter doesn’t happen again.

Legacy

The introduction of Ellen’s Law was backed by cycling advocates across the province in the wake of Ellen’s death.

Rallies were held in front of the legislature as well in Moncton and in Saint John to put pressure on the province’s then-Liberal government to pass it through the legislature.

The legislation was celebrated by advocates when it was passed in 2017.

The law, also known as the “one-metre rule,” costs New Brunswick drivers who don’t give cyclists enough space a $172.50 fine, along with three demerit points.

But the results of the legislation have been less than successful.

Only three people have ever been tried under Ellen’s Law, according to New Brunswick’s Public Prosecution Service.

Two of the people were successfully prosecuted and one was acquitted, although the department stresses that if an individual was issued a ticket and paid the fine before the court date it would not be included in the figures provided to Global News.

“(The New Brunswick government) is very proud of Ellen’s Law, and of its ongoing efforts to remind motorists and cyclists to share the road safely,” says Coreen Enos, a spokesperson for the Department of Justice and Public Safety.

“We also respect that there are bicycling enthusiasts who believe government additional changes to the law could make roads safer for people on bicycles.”

Cycling advocates say Ellen’s Law was cause for celebration but that it was by no means a silver bullet in solving the problems cyclists face in New Brunswick.

A memorial honouring New Brunswick cyclist Ellen Watters near Apohaqui, N.B.

Tim Roszell/Global News

A timeline provided by the New Brunswick Cycling Coalition, an organization of advocates in the province, indicates that many of its suggestions provided to the provincial government during the drafting of Ellen’s Law were not implemented in the legislation.

A bicycle safety strategy working group was formed in the aftermath of the legislation’s creation. It was meant to provide advice to the justice and public safety minister on how to design and develop policies in New Brunswick that would make roads safer for cyclists.

The working group presented its recommendations to the public safety minister in 2018, with recommendations for rules around dooring and giving municipalities the authority to designate certain sidewalks as bike-friendly.

But any efforts to implement changes were halted as the provincial government changed from the Liberals to Blaine Higgs’ Progressive Conservatives in late 2018.

The coalition, one of the many organizations advocating for change, has repeatedly met politicians and government officials over the past four years to discuss possible changes to the province’s Motor Vehicle Act but has so far been unsuccessful in persuading politicians.

A press release sent out by a cadre of New Brunswick cycling organizations during the province’s most recent election even referred to the province’s Motor Vehicle Act as the most outdated in the country.

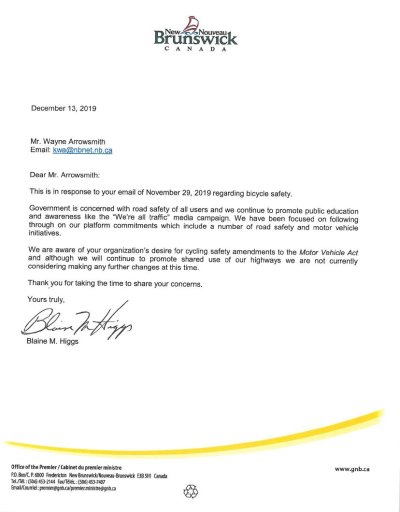

Global News reported in January that Higgs had signed a letter in 2019 addressed to the Saint John Cycling group saying the government will continue promoting road safety, but is not planning on making any changes to the MVA.

A letter sent to the New Brunswick bicycle safety working group by Premier Blaine Higgs in December 2019.

Provided

But change may be on the horizon. Enos told Global News in a statement that the province continues to “maintain a dialogue” with the cycling working group.

Enos says the province is “committed to improving bicycle safety, and a meeting has been set for (January 2021).”

Read more:

N.B. cyclists continue to push for Motor Vehicle Act amendments

The present

Nancy Watters says the ability to revisit her daughter’s story and the legacy she has left behind has been cathartic, giving her a sense of closure and an opportunity for something she never had.

“You know how after a trial the victim’s family can give a report, the impact statement?” she says. “I feel what you’re doing is that for me.”

Nancy says she treasured every moment she spent with her daughter and for that reason, she’ll continue to push for legislation that protects New Brunswick’s cycling community.

“I’m so thankful I had her for those years here because she moved from being a teenager into an adult so that we had lots of good conversations and times together as she matured,” she says.

“If you’ve ever started a fire and tried to get the fire starting from nowhere — a spark growth, a little bit of a match starting up — that was Ellen.”

With files from Global News’ Tim Roszell