As Canada enters the early stages of influenza season, experts warn that Australia’s record-breaking flu outbreak may offer a troubling glimpse of what might come.

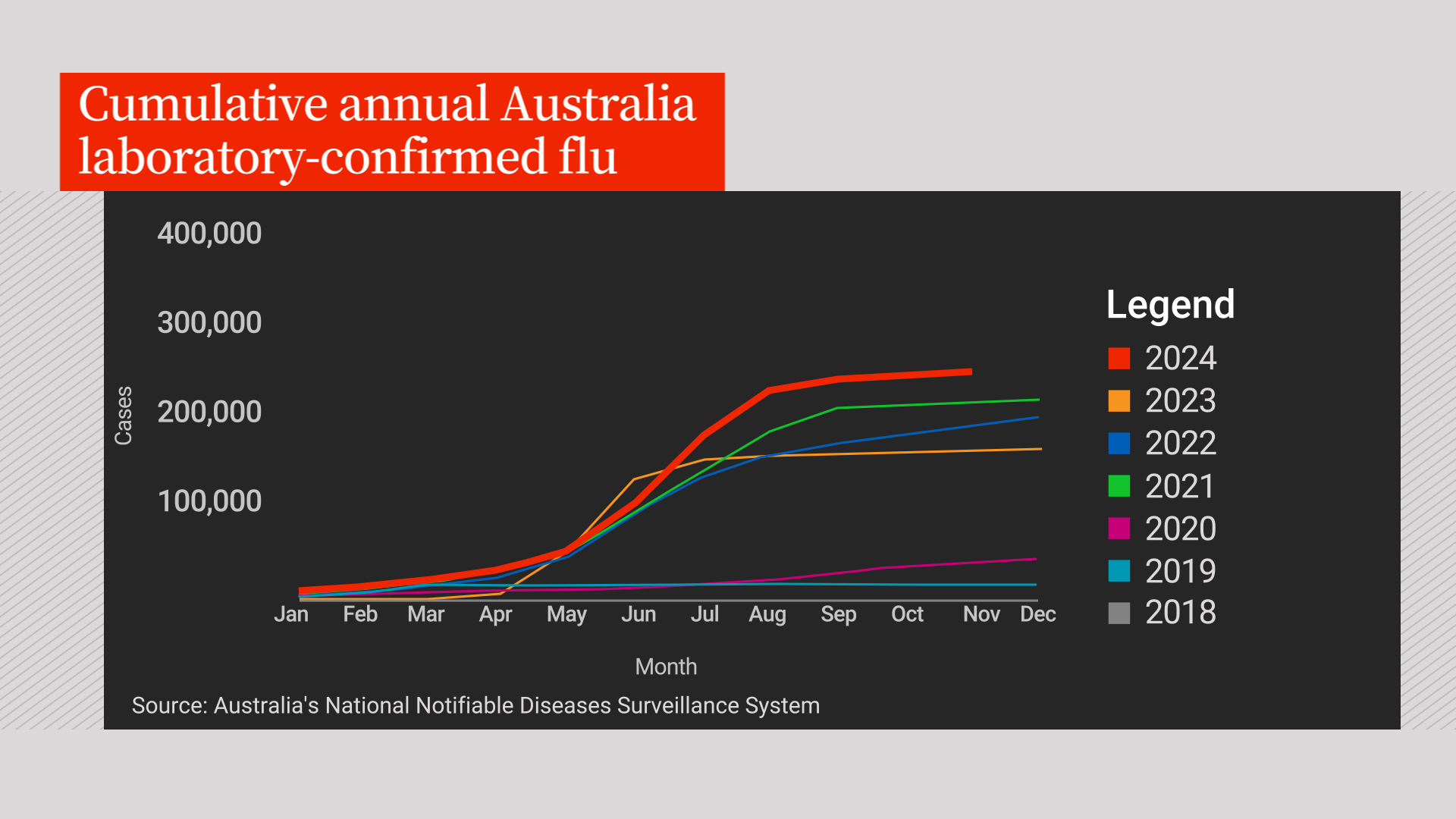

The latest data from Australia’s National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System shows the country recorded 352,532 laboratory-confirmed flu cases this year, eclipsing the previous high of 313,615 cases in 2019.

Flu vaccination rates in Australia have also steadily declined, with national data revealing a consistent drop over the past two years.

“It’s a cautionary tale. People forgot to get their vaccines, the vaccination rate was too low and this led to an increase in the number of cases,” Dr. Brian Conway, medical director of the Vancouver Infectious Disease Centre, told Global News Edmonton on Wednesday.

“Deaths with influenza were up across the board for every age group. And a 15-per cent reduction in vaccination rates led to an increase in cases and an increase in mortality,” he said.

Seasonal influenza typically circulates during the winter months, with Australia’s flu season running from their winter of May to October, while in Canada, it spans from October to May.

In Australia, the dominant flu strain this season was the A(H3N2) virus, a subtype of influenza A known for causing more severe illness, particularly among older adults, young children and people with weakened immune systems.

In Canada, the country’s weekly flu watch data says it is too early in the season to confirm which strain is the dominant one, but influenza A(H1N1) remains the most commonly-detected strain. The data also shows the percentage of tests positive for influenza remains below the seasonal threshold but is showing early signs of an increase in Canada.

While trends from the southern hemisphere’s flu season can sometimes offer insights into Canada’s influenza season, they are not always reliable predictors, said Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious diseases specialist based in Toronto.

“Influenza is predictably unpredictable. It’s not entirely clear what the influenza season is going to look like, as there’s always some twists and turns,” Bogoch said. “Just because the southern hemisphere had a certain flu season does not mean that we’ll replicate that.”

Why was Australia’s flu season so bad?

Australia’s 2024 influenza season marked a significant surge, surpassing last year’s total with more than 351,000 confirmed cases, up from 289,000 in 2023.

This comes as the country’s Immunisation Coalition’s national survey found that fewer Australians are choosing to protect themselves through vaccination. The declining vaccination rates raise concerns about the country’s preparedness for future flu seasons and highlight a growing public perception that influenza is not a serious disease, the coalition stated.

“The record number of cases should be a wake-up call. Influenza is not just a bad cold; it can have severe consequences, particularly for vulnerable populations. Yet, our surveys indicate that many Australians are disengaged and feel vaccination is unnecessary. This puts the whole community at risk,” Rodney Pearce, chairperson of the Immunisation Council, said in a statement on Nov. 5.

The influenza vaccine helps protect both individuals and the community by reducing the spread of infection, Conway said.

The goal is to achieve herd immunity, he said, which requires at least 50 per cent of the population to be vaccinated.

“This creates a higher level of immunity in the community, reducing overall disease spread. However, in Australia, vaccination rates fell below this threshold, leading to a higher number of flu cases,” he said.

Conway suggested that one of the reasons Australians have been reluctant to get their flu shot is the vaccine fatigue that has emerged since the COVID-19 pandemic.

For example, a national survey revealed that 54 per cent of Australian respondents did not perceive influenza as a severe disease, while 45 per cent of parents were unaware that vaccines were available for their children.

Although data shows that influenza numbers in Australia have reached record levels, Bogoch noted that many questions remain unanswered. While the poor vaccine uptake may be a contributing factor, other variables could be at play, such as whether health-care professionals conducted more tests this season, leading to a higher number of reported cases.

Vaccine effectiveness could also be a contributing factor, though data on this typically doesn’t become available until a few months after flu season, Bogoch said.

What’s in store for Canada?

Influenza vaccines in Canada have already begun rolling out — and it’s not too late to get yours — but it is still too early to know the exact uptake in numbers.

However, 2023 to 2024 national data shows influenza vaccination coverage was 42 per cent, which was similar to the previous season (43 per cent).

While vaccination coverage among seniors (73 per cent) is closer to the coverage goal of 80 per cent, only 44 per cent of the adults aged 18 to 64 years with chronic medical conditions received the flu shot in Canada, data showed.

The most common reason for getting the flu shot was to prevent infection (23 per cent), whereas the most common reason for not getting the flu shot was the perception that the vaccine was not needed (31 per cent).

And despite most people agreeing that the flu shot is safe (87 per cent), 43 per cent of adults mistakenly believed that they could get the flu from the flu vaccine.

Although vaccine numbers were lower than what was expected, Conway said it still helped mitigate the risk of influenza in the community.

“We still had 100,000 cases, several hundred deaths, and several thousand hospitalizations, but we could manage it and it was an average flu year. We really cannot afford for that to go up, so we need to go out there and get our shots and do all these other things to protect ourselves and others,” he stressed.

Canada is still in the early stages of its influenza season. While current case numbers are low, Bogoch said cases will rise as the season progresses.

“It just starting to take off, but it hasn’t started earlier. I saw some data that suggested it might have started a bit earlier in Australia, but that didn’t happen here,” Bogoch said.

“I think we’re going to get it and of course, we’re going to get COVID, and it’s probably all going to peak at the same time as flu and RSV, and we are probably in for a tough time come January or February.”